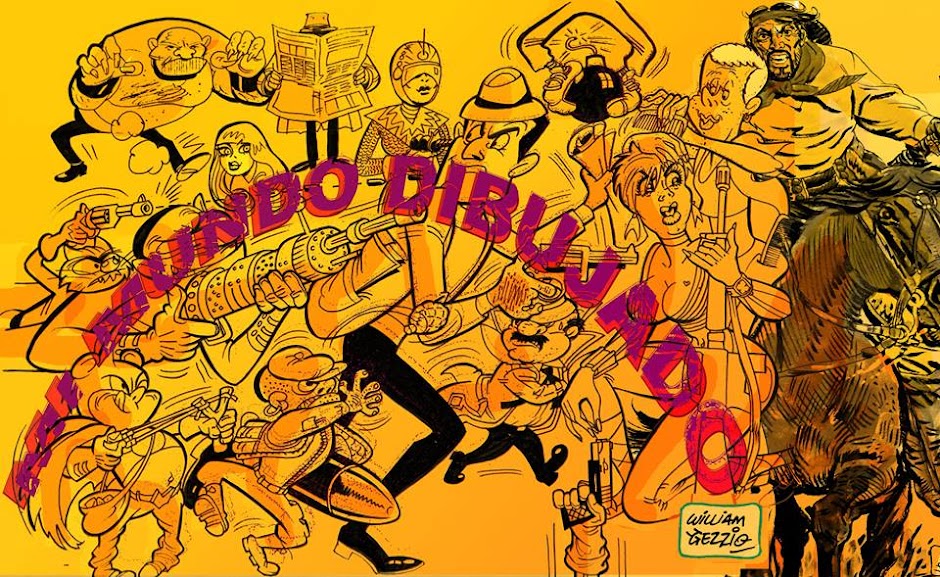

Dibujando acorde a la temática

Aquí pongo dos ejemplos radicalmente opuestos que muestran que en cada tapa debí emplear una forma diferente de dibujo y pintura acorde a la revista en que iba a ser publicada.Tapa para Quimera

Quimera fue un suplemento de historietas del diario La República donde se publicaba variados temas.

Quimera fue un suplemento de historietas del diario La República donde se publicaba variados temas. En las reuniones que hacíamos para confeccionar cada número, se encargaba a alguno de los integrantes el dibujo de tapa. Esa vez me tocó a mí por lo que pensé en variar mi estilo ; había publicado temas gauchescos y uno de detectives y ya tenía otra historieta en producción de un fotógrafo con tintes dramáticos.

Todos teníamos amplia libertad en la elección de los temas de tapa, por lo que se me ocurrió hacer algo diferente y creí que un tema de ficción sería justo.

Boceté varias miniaturas hasta que me gustó una y la amplié ligeramente, buscando más la composición que el resultado final.

Luego comencé por el personaje principal y los secundarios que se me ocurrieron antropomórficos, una mezcla de humanos y animal, pero en estado semisalvaje, pero en algún mundo lejano, por eso puse una especie de luna o planeta en el fondo.

Par darle más ilusión de belicismo, unas imágenes como de un ejército entre sombras, se divisa sobre el pico de una montaña cercana.

Elaboré los dibujos por separado y los pinté en photoshop, luego armé todo en la medida de la tapa, previendo el espacio superior para el título que lo pondría el diseñador de la revista.

En tonalidades calientes de los rojos y violetas pinté todo. Luego le apliqué un efecto radiante al fondo que luce como una explosión . Los rayos sirven para centrar la visión del lector en las imágenes principales, completando una composición asimétrica.

Y al final quedó pronta y enviada para la revista.

Tapa para El Escolar

Esta otra tapa es completamente apuesta, ya que era para un suplemento infantil y el motivo a ilustrar era "niños jugando con globos". Pensé en un enfoque desde abajo, como si un niño presente estuviese viendo la escena.

Al suelo le hice una curvatura exagerada, eso da la ilusión de perspectiva, bastante falseada por cierto, pero funcional en este caso. Lo del perro y el gordito sobre los globos es una humorada, que en este tipo de dibujo es conveniente utilizar.

Al suelo le hice una curvatura exagerada, eso da la ilusión de perspectiva, bastante falseada por cierto, pero funcional en este caso. Lo del perro y el gordito sobre los globos es una humorada, que en este tipo de dibujo es conveniente utilizar.La composición asemeja un triángulo truncado, compensado por los globos que aunque están volando también tienen su propia estructura pensada previamente, como lo muestro en el boceto.

Hice un dibujo lineal, lo más cerrado posible y luego lo pinté en photoshop, evitando el exceso de efectos, porque en esta tapa no creí conveniente usarlos.

Luego la envié a la redacción de la revista donde le aplicaron el logo y los textos, ¡los textos! Nunca entendí porqué los diseñadores que me tocaron "en suerte" insistieron en taparme partes de mi dibujo con grotescas tipografías...

En este caso -ya me había quejado- apenas tocaron la cara del "gordito volador".

lineal en tinta

Copia que imprimí para ver cómo quedaría la impresión final y hacer algunos ajustes,

ya que la pantalla de la computadora "engaña" un poco.

Resultado final